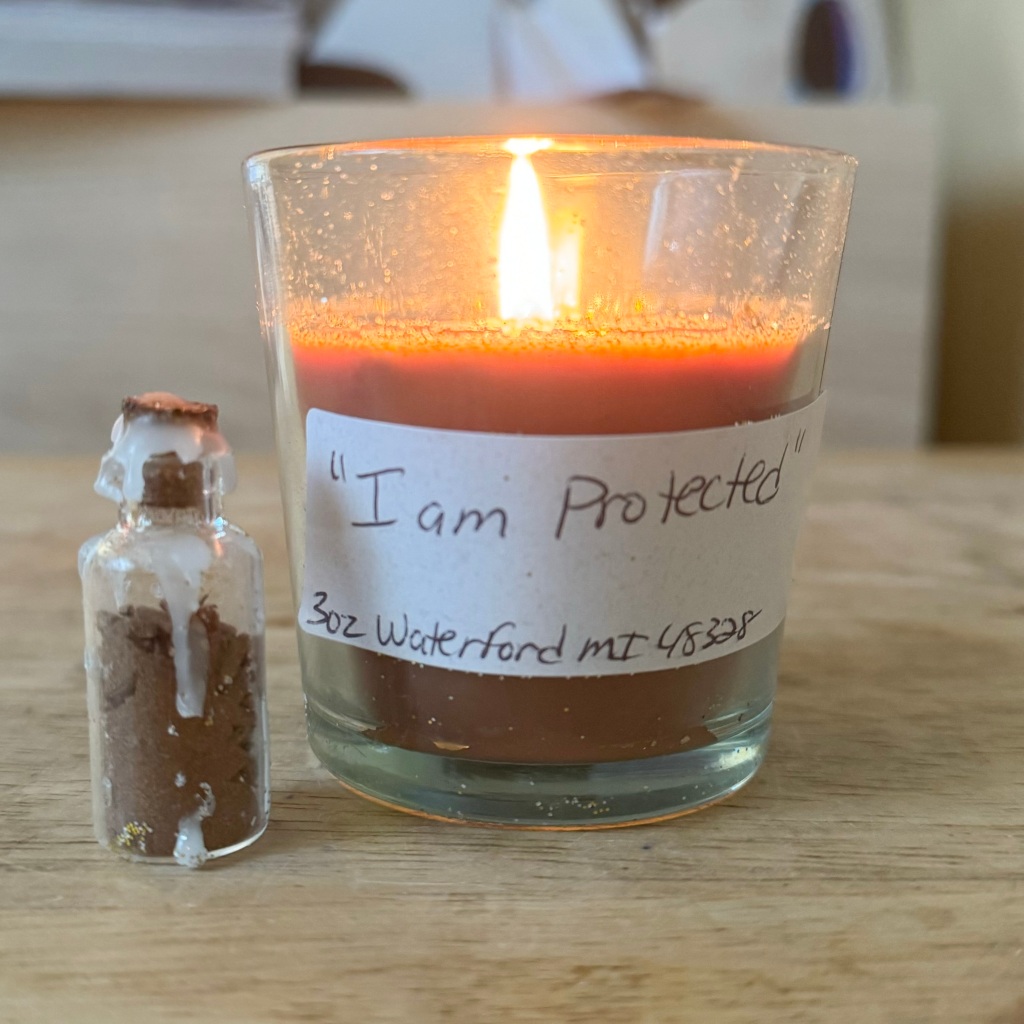

There is a fire in my belly, moving from the candle in front of me, in through my palms, up to the area of my heart, and down to my belly where I am breathing with purpose. Each breath provides oxygen to fuel the fire that has been building for some time, moving me to speak, act, and share.

Living in the world with multiple intersectional identities is a complex experience, even more so during an election year. With each bill introduced and story shared by news organizations, we are moving either closer to or farther away from inclusion, equality, and justice. We are moving closer toward a world where our humanity is recognized as valid and whole, or farther away from this reality, and toward more discrimination, hatred, and exclusion.

To paint a picture: A few days ago, former president Donald Trump said that there will be a bloodbath if he loses the election in November. The ACLU is mapping 479 anti-LGBTQ bills so far in 2024. As of mid-February, almost 5,000 people have died from gun violence in the U.S., and here in North Carolina, the Republican gubernatorial candidate is a Holocaust denier who believes that gender diverse people (like myself, my child, and many clients) are filth who should use the bathroom in the backyard like the dogs.

For people who hold multiple marginalized identities, these currents of hate are more than a cerebral exercise, mere politics, or an opportunity for good-hearted social change efforts. Whether we are consciously aware of it or not, the things so many of us are going through in the United States are lived experiences of ongoing trauma, terror, and rage within our bodies. We make it through our days by riding roller-coasters of adrenaline, norepinephrine, and cortisol, leading to tightened muscles, inflammation, stress, and a host of health concerns.

Far from political, these human rights concerns live in our cells as threats and violations. Navigating them is an everyday purpose we aren’t given a choice about, one rooted in our very survival, or our children’s survival. To add more to our already full plates, even in the midst of confronting these realities, most of us are faced with an expectation to show up to work, school, and the world in general as if nothing is awry.

Unlike allies, we don’t get to do some good and then take a break, as our identities are not something that we can check at the door. What we can do is focus on intentionally cultivating spaces with others who hold the same and similar identities and lived experiences, spaces where it is safe to exhale, process our emotions, and let our guards down. We can offer and receive desperately needed support in spaces where those who are threats to our existence are not welcome.

We can doggedly pursue our dreams, the passions on our hearts, and release our gifts for the world in ways that feel nourishing, caring, and compassionate toward self and others. We can drink in mercy, unconditional love, and healing energy, even as we share these same things with those around us.

In the midst of it all, as we process trauma while still living in it, may we find ways to slow down, intentionally setting aside time to rest and heal, replenish our emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual reserves. As we rest, may we offer ourselves kindness and gentleness, being patient as our nervous systems calm so that we can return to spaces and paces of intentional action.

For a place to start, I find this version of “Om Mani Padme Hum” to be soothing and restful. Sometimes, I listen to it as I breathe gently and scan my body to release any held tension, then breathe care through the area of my heart, reminding myself that my pain is valid, I am loved, and I am allowed to take all the time I need to rest and replenish.